Way of Taiji

Speaking of Taiji Quan (太極拳), we touch upon one of the most complex concepts of Chinese culture, a great art whose heritage has been formed over the centuries and which has a philosophical, practical, and alchemical aspect. From whichever angle one looks at Taiji Quan – mythological, historical, philosophical, martial, medical – it is all part of one whole.

It is impossible to isolate a generalized single doctrine of Taiji, especially within a single direction, and not considering the diversity of the existing styles would limit the concept of Taiji Quan. An additional challenge for understanding is the mentality of those who practice Taiji Quan, and historical narratives are more likely to divert from understanding rather than to clarify the topic.

A big challenge is the lack of practice experience or misaligned effort, where even the wrong shoes can lead the practitioner in the wrong direction. But the most significant difficulty lies in the misunderstanding of the mentality of Taiji Quan. Many people refer to Taiji Quan as an inner art, but the inner art is characterized by the brain’s ability to operate processes, not by the simple practice of a form.

When we are faced with the question of determining the direction that allows us to clearly express the practical possibilities of Taiji Quan these days, we are confronted with three problems:

- A confusion of the teaching by physical culture, sports, or misrepresented ideas that dominate the space.

- Lack of a tradition of learning, lack of schools.

- Insufficient understanding of the treatises that have reached us, including Chen Xin’s (陳鑫, 1849-1929) “The Illustrated Canon of Chen Family Taijiquan”, also “Chen Shi Tai Ji Quan Tu Shuo” (陳氏太極拳圖說), which presents the knowledge of the development of Taiji Quan in 13 forms.

The understanding of the tradition as a school should be associated specifically with the Chen style (Chen Shi, 陳式), the tradition of which goes back to the time of the legendary founder of this dynasty, Chen Bu (陈卜), born in the 14th century. The utmost importance of this practice lies in its connection with the knowledge of the great Taoist immortal Zhang Sanfeng, (張三丰) who created the Taiji matrix.

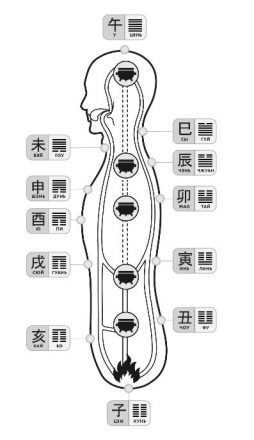

The main value of this knowledge that we can perceive today is how to strengthen the bone marrow. Everything else is a consequence. The ability to cultivate Jing and bone marrow is what they call “the magical powers of Taiji”.

All this knowledge is embedded in the old form of Lao Jia (老架). It is a profound geometric art whose possibilities have no limit, where the power of Jing-Shen energy is developed, making Taiji Quan the ultimate art of developing strength in movement.

When practicing a form, it is very important what kind of task we are dealing with. If we don’t have a task, then we’re just working the muscles and developing the reality associated with them. So, the question is not so much who we practice with, but what we actually practice.

Achieving effectiveness in Taiji Quan is not easy, unless, of course, we consider relaxation as a result. First and foremost, we need to understand what it means to improve ourselves by practicing Taiji Quan, not just expecting an effect from performing the forms. To do this, it is important to accept the following:

- It is important to understand the physics and energy of motion.

- Taiji Quan is the basis of proper movement, which promotes the alignment of geometry and makes any kind of movement a practice of cultivating energy.

- Taiji Quan is all about mindfulness. In today’s reality, it doesn’t make sense to simply repeat the practice after the master – you have to be able to set goals for yourself and achieve them.

- The art of proportion.

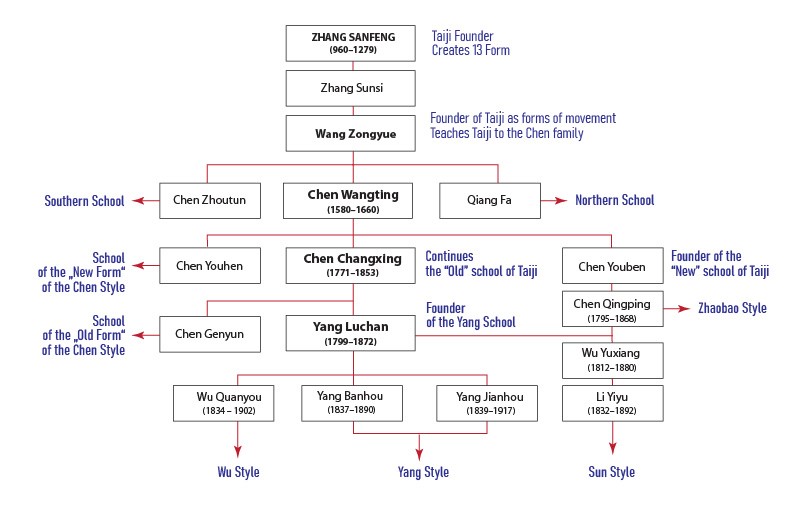

The theory and practice of Taiji Quan are based on centuries of history. The development of this art is associated with many legendary people. The succession of knowledge and the history of Taiji Quan can be represented as follows:

Practically each of these masters offered different ways of comprehending the art of Taiji Quan, and each method was determined by its tasks. During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) there was a structuring of all Taoist knowledge and the legend associated with Zhang Sanfeng was formed, covering a period of more than 300 years. According to the legend, it was Zhang Sanfeng who created the set of movements now known as Taiji Quan. But it was Chen Tuan (陳摶, 871-989) who introduced the art of Taiji in a schematic way on Mount Huashan.

Chen Tuan formulated the teaching of the development of motion in space. Although many people repeat his basic postulate “motion at rest or rest in motion”, in reality, it is difficult to understand the energetic principle of this process. It is linked to the principles of breathing, building proportion in the body, and circulation of energy. The great significance of Chen Tuan’s legacy is that he pointed out the categories that essentially classified the idea of Taiji.

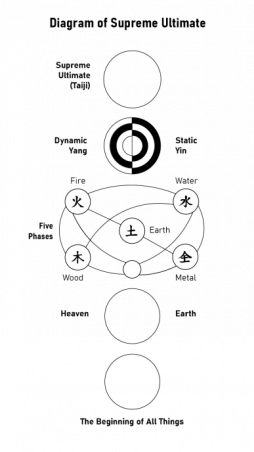

The symbol known as “Yin-Yang” is not a Taoist symbol in the literal sense, but exactly the symbol of Taiji, symbolizing the connection between Earth and Heaven, that is, space and time (numbers 8 and 12). Each of the 12 Taiji forms reflects a sector consisting of a three-dimensional body and contains 8 efforts “a mini-cube inside a cube”.

In two-dimensional space, the geometric relationship of 8 and 12 appears as the basis of movement, the effort in the three lower joints (the lower trigram) and the three upper joints (the upper trigram). And these are not just symbols, but a code for the energy going in or going out.

The body itself is aimed at reflecting the harmony between Heaven, Earth, and Man – so a detailed correspondence was established in the movements between the trigrams, hexagrams, and the human body. Each position is a certain geometric figure, working on the diagram of the Supreme Ultimate.

All constructs begin with the scheme of Infinity. The source of Taiji (太極, the Supreme Ultimate) comes from the Infinite.

The development itself is divided into the following factors:

- The Way of Heaven. Reminiscent of movement in a microcosmic orbit. It is characterized by the nurturing of the channel of control.

- The Growth of the Earth. Relying on the axis. It is characterized by the cultivation of the channel of conception.

- The Human Level. It is characterized by the ability to transform when one has learned the forms The Three Changes (san zhifa) and Back to the Source (gui zang).

At the same time, Taiji Quan implies several methods that process the effort in different ways. So, despite the fact that the modern presentation of Taiji Quan generally correlates with the traditions of Chenjiagou (the ancestral Chen family village), the Yang style (Yang Shi, 楊氏), Wu style (Wu Shi , 吳氏), Wu Yuxiang (武 禹 襄, 1812-1880), Wu Jianquan (吴 鉴 泉, 1870-1942), and Sun style (Sun Shi, 孫氏) also present their interesting methods and approaches to understanding Taiji Quan.

Of course, to talk about which style is better for Taiji Quan is an unreasonable and unnecessary task. In this case, since the Chen style is the earliest movement, all later styles may be considered to have originated from it.

The total number of styles is, of course, much greater, and this is mainly due to the diversity of understanding of the practice of developing the spiral movement, or the art of Silk Reeling (Chan Sijin, 纏絲勁), which has been known since the Chen Wangting (陈王庭, 1580-1660). It is a highly complex art that was already impossible for a novice to master.

The art of Silk Reeling, which is unwinding and coiling by the practitioner, is a special practice of developing inner elasticity through the materialization of Jing energy. It is a special inner effort without which it is impossible to know the art of Taiji Quan. Every movement of drawing silk from a cocoon aims to generate energy, which is then mastered by Fa Jin (發勁 – throwing power), which leads to the concept of the infinite and the development of special abilities.

There are also directions related not to the Chen family, but rather to other inner styles (Bagua and Xing-Yi), which not only develop similar inner principles but are also visually similar (although they form different efforts). From the point of view of the Silk Reeling practice, Bagua Zhang ( 八卦掌) is closer to Taiji Quan, and from the point of view of the Fa Jin practice – Xing Yi (形意).

Thus, the three pillars on which the art of Taiji Quan is built are:

- The art of creating the Unified Body that is formed around the dantian

- Mastering the spiral movement

- The art of throwing power

Video

Lecture by Oleg Cherne “Ideology of practices in motion”

Lecture by Oleg Cherne “Taijiquan – lost knowledge”

Bone Marrow Regeneration